I must admit, one of my all time pet peeves is when engineers do not implement their user authentication service in the right way to be defendable against an attack.

Take for the instance the recent hack against Zomato in which they had 6.6m hashed user passwords stolen. The real problem here is not that the hashed passwords were stolen as such (the hackers should be not able to do anything with them) – its whether the hackers could have set the hashes for the passwords and therefore take over any account they wanted (or modified anything else). Also it looks like they got away with peoples email addresses as well, which given the soon to be enforced (25/5/18) EU GDPR regs could prove a trigger for a rather large painful & probably terminal fine.. (see here for more details on this, if you run a startup or business online you need to read it now).

It is not that hard to do user authentication correctly and in a way which is secure – and I’m going to show you one way to do so right now.

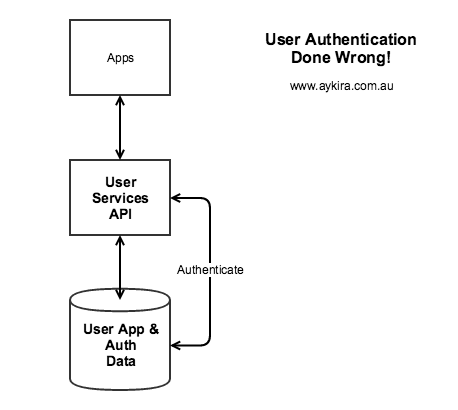

First the wrong way…

Whats wrong with the picture on the Right? If you see nothing wrong, PLEASE do not have anything to do with user authentication – take up sock knitting or woodwork instead, stay well away from anything online security related!

Whats wrong with the picture on the Right? If you see nothing wrong, PLEASE do not have anything to do with user authentication – take up sock knitting or woodwork instead, stay well away from anything online security related!

First, let me detail the likely way this has been implemented:

- The Authentication Data (be it hashed or not, does not matter) ‘lives’ right alongside the App Data for each user. Chances are the same DB credentials are used to get access to the whole record…

- The User Services API is probably quite a ‘wide’ API given it has to deal with all the user app data requests as well as all the user auth requests. So app data code is ‘mixed in’ with user auth code…

- The User Services API probably has a mix of endpoints that require different rights or permissions for operations to be enacted across either singular or sets of user accounts.

What is the practical upshot of all this code, rights and credentials inbreeding? Several things:

- ANY change to the User Service API could open up a security ‘hole’ to provide access to the Auth data – SQL injection is probably the most likely vector.

- Another is a ‘misalignment’ in rights assignment, e.g. something that requires admin access gets inadvertently open to all OR it’s trivial to ‘game’ the rights management logic to become an admin.

- ANY change to the User Service API network environment could open up a hole to the database and beyond…

- There is no inherent structure to the system that stops cross talk between app data and auth data – by this I mean the loading on the API for app data could interfere with that for the auth function – in other words an easy drive by DDOS can happen and everybody is locked out at once.

- Also who ever is developing the User Service API is most likely to also have access to all the Auth info as well, if not be responsible for how the auth process works, this makes the integrity and security of the individual(s) so ‘blessed’ paramount.

Now this anti-pattern of holding app and auth data together is pretty much all over the place, you will find it in nearly all Open Source CMS’s (WordPress comes immediately to mind, hmm…) and most ‘shake and bake’ frameworks as well do this automatically for you as well.

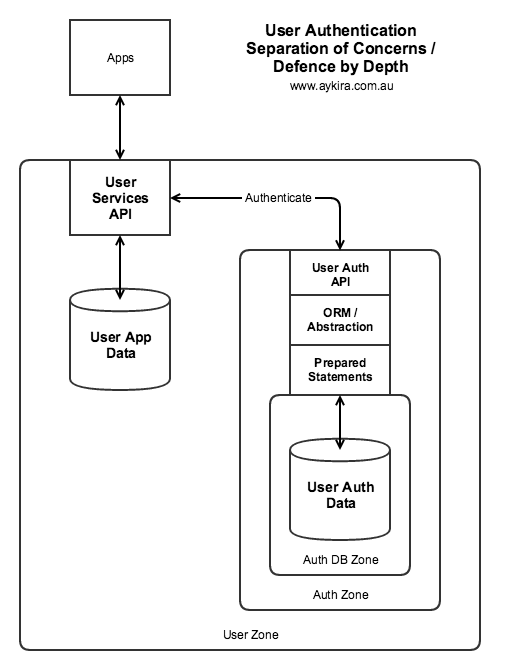

Now the Right Way..

See the new diagram on the right..

See the new diagram on the right..

First off the ‘function’ of Auth has been forwarded out to a completely separate subsystem which can only be seen by the User Services API, this could be done at a higher layer by a router or forwarding agent, the exact mechanism doesn’t matter – what is key is the User Services API and its database holds no info whatsoever as concerns User Auth.

So, if a hacker gets into the User App DB below it, they have no passwords or emails to play with. Yes, you still got hacked, but you don’t have to force everyone to change their passwords.

Secondly the User Auth Service lives in its own little network ‘bubble’ or subnet – nothing goes in (or out) unless specifically allowed (this is important).

Thirdly, the User Auth Service is made up of distinct layers, with the golden rule being that any queries used are prepared and enacted well away from the ‘front’ of the service – this way SQL injection becomes much harder by deliberate design.

Fourthly, the actual User Auth DB itself lives in its own little subnet and can only be ‘seen’ by the User Auth Service back end.

Fifthly, any changes to the User Auth Service needs to be reviewed by someone else whose job function is to do security and sign it off prior to it going into production. This way ‘gotchas’ can be tested for and found before they hit production. Note: the same engineer cannot write code and review it for security, it needs a distinct pair of eyes to be sure.

Isn’t this overkill?

Depends how much you value your brand at the end of day and how many ‘eggs’ you want to put in the one basket. BTW the techniques applied here are Defense By Depth and Separation of Concerns – both fairly standard ways of being more secure using architecture design techniques.

What is the cost of this?

How much would this cost? Just looking at the ongoing costs, and knowing auth data is usually ‘smaller’ than the app data; a small business with a decent online presence would pay say $50 per month to a cloud provider (like Amazon) for this. Which is a lot less than the brand damage and disruption caused by an auth hack.

The other ‘win’ with this approach is you made the User Auth API into what I term potential ‘first class service’ in that you can freely change how you implement auth independently of anything else. For instance you could set up a new service or auth process for other usage cases. You could provide additional security or alerting without anyone else in your system architecture being impacted. It’s also an approach that would make it a lot easier to get security audit approval by a third party, as it is evident through design you have taken security into account.

Alternatives

You could actually completely ‘farm out’ your auth to a trusted third party (say via OAuth or OpenID) but this means your security surface in effect ‘extends’ around whoever you have decided to provide that function – if they are very big and very trusted that could be a good idea (especially if the Auth gives you access to other goodies as well). Although you will still need a system place to keep tokens and associated configuration, so a similar form of the above separation would be a good idea to have – to avoid having to cancel down all your tokens in the event of a hack. Also be careful to not get too ‘bound’ to the third party, as you could create a ‘lock-in’ situation, whereby it becomes prohibitively expensive to move to another solution later on as the third party services are so lightly integrated into your systems; in other words what looks a good idea now could be problematic in the future. In such situations I tend to ‘wrap’ the integration with the third party, so its easier to change later on. Remember the third party might discontinue their service or change it in a way that no longer suits your needs.